FULL ARTICLE:

AIDS Behav. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 May 1. Published in final edited form as: PMCID: PMC5926187 NIHMSID: NIHMS960920 Stigma

and Conspiracy Beliefs Related to Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and

Interest in Using PrEP Among Black and White Men and Transgender Women

Who Have Sex with MenThe publisher's final edited version of this article is available at AIDS BehavSee other articles in PMC that cite the published article. AbstractThe

HIV/AIDS epidemic in the US continues to persist, in particular, among

race, sexual orientation, and gender minority populations. Pre-exposure

prophylaxis (PrEP), or using antiretroviral medications for HIV

prevention, is an effective option, but uptake of PrEP has been slow.

Sociocultural barriers to using PrEP have been largely underemphasized,

yet have the potential to stall uptake and, therefore, warrant further

understanding. In order to assess the relationships between potential

barriers to PrEP (i.e., PrEP stigma and conspiracy beliefs), and

interest in PrEP, Black men and transgender women who have sex with men

(BMTW, N = 85) and White MTW (WMTW, N =

179) were surveyed at a gay pride event in 2015 in a large southeastern

US city. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were

completed to examine factors associated with PrEP interest. Among the

full sample, moderate levels of PrEP awareness (63%) and low levels of

use (9%) were observed. Believing that PrEP is for people who are

promiscuous (stigma belief) was strongly associated with lack of

interest in using PrEP, and individuals who endorsed this belief were

more likely to report sexual risk taking behavior. Conspiracy beliefs

related to PrEP were reported among a large minority of the sample (42%)

and were more frequently reported among BMTW than WMTW. Given the

strong emphasis on the use of biomedical strategies for HIV prevention,

addressing sociocultural barriers to PrEP access is urgently needed and

failure to do so will weaken the potential benefits of biomedical

prevention. Keywords: PrEP, HIV prevention, Stigma beliefs, Conspiracy beliefs IntroductionThe

current US HIV epidemic calls for urgent attention in addressing rates

of HIV transmission among men and transgender women who have sex with

men (MTW) [1].

Of great concern, are the race-related disparities in HIV transmission,

in particular, the exceedingly high rates of HIV infection among

Black/African–American MTW (BMTW) compared with White MTW (WMTW). For

example, although HIV prevalence is elevated among MTW compared to the

general population, rates of new HIV infections among BMTW are 6.0 times

higher than rates among WMTW [2]. It is estimated that 61% of BMTW could be living with HIV by the time they reach age 40 [3]. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), or the use of antiretrovirals such as Truvada®, to prevent HIV transmission among HIV negative persons at-risk for HIV is a highly effective option for HIV prevention [4, 5].

Although PrEP for HIV prevention was approved by the US FDA in 2012,

uptake of PrEP among individuals in-need has been limited [6–8].

In order for PrEP to have a population-level impact on incident HIV

infections, scale-up efforts must be prioritized and barriers to

implementation need to be addressed. Broader implementation of PrEP for MTW could potentially result in a substantial decrease in incident HIV infections [9].

Multiple factors, however, have impeded access to and interest in

taking PrEP among MTW. Main barriers to use include a lack of

wide-spread messaging to promote PrEP in communities of elevated HIV

prevalence, costs associated concerns among individuals with no/limited

insurance, lack of prescribing providers [10], concerns regarding side-effects and long-term use, and sociocultural barriers to use [11], such as experiences of stigma [12, 13] and other negative beliefs about its use [14]. There

is increasing concern for the latter barrier, i.e., sociocultural

barriers to PrEP interest and use. Popular press reports regarding PrEP

have described individuals using PrEP as “Truvada Whores”—a disparaging

term that associates promiscuity with use of PrEP [13, 15]. These commentaries have generated considerable discussion on social media [16],

yet little empirical research has assessed what influence these

sociocultural barriers have had on individuals’ interest in PrEP. These

potential barriers to PrEP interest and use are not well-understood as

this topic is a novel area of research focus. In implementation

research, understanding how communities respond to prevention

strategies, either by adopting or rejecting them, is critical, but we

have very limited information on this topic with respect to PrEP. Based

on what is known from informal reports and empirical research on how

PrEP has been embraced by communities, stigma related to PrEP uptake

appears to be an important sociocultural barrier to PrEP interest [13].

Briefly, stigma is a social construction where social devaluation

occurs through a process of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status

loss, and discrimination [17].

This process serves as a way to maintain social power structures by

subordinating those whose possess devalued characteristics and elevating

those who do not. In the case of PrEP, the emergence of negative

stereotyping—an important component of stigma—towards individuals who

use PrEP deserves further attention and understanding [18]. It

is known that the negative labeling of groups (in this case those who

use PrEP) can dissuade interest in being part of such group. For

example, simply using PrEP implies concern for risk of HIV transmission,

which, in turn, may imply engagement in sexual risk taking behavior.

Engagement in sexual risk taking has a long-standing history of

violating perceived social mores. Further, stigma by association is

also known to occur when an individual experiences stigma as a result

of being connected to a stigmatized person or group [17].

Negative interpersonal associations have the potential to affect how

individuals are perceived. In the case of PrEP, individuals may be

concerned about using an antiretroviral for HIV prevention if they

associate PrEP use with persons living with HIV—a highly stigmatized

group. These societal processes have stymied HIV prevention and

treatment efforts since the beginning of the epidemic [18, 19] and has the potential to inhibit PrEP implementation. Along similar lines, conspiracy related beliefs about biomedical approaches to HIV prevention [20–22]

are also likely to affect PrEP implementation, but research in this

area has yet to be conducted. Conspiracy beliefs are typically thought

to imply that organizations or individuals in power furtively manipulate

events in a self-serving manner. Conspiracy beliefs in HIV treatment

have been attributed to a historical legacy of mistreatment of race

minority populations by medical establishments [23].

For example, it is well-documented that conspiracy beliefs about

biomedical strategies—primarily antiretroviral use—for HIV treatment are

prevalent and related to poor HIV-related health outcomes,

particularly, among HIV positive, race-minority individuals [24].

Given the existence of these beliefs in HIV treatment efforts, it is

probable that these beliefs would affect PrEP interest as well. Study ObjectivesThe

primary focus of the current study was to assess factors associated

with interest in using PrEP. This area was examined by evaluating the

relationships between sociodemographic variables, health care, PrEP

stigma beliefs, PrEP conspiracy beliefs, and sex behaviors (independent

variables) and interest in using PrEP (dependent variable). Due to the

race/ethnic disparities relating to HIV transmission, results were

reported for the whole sample and separately by BMTW and WMTW. MethodsSetting and ProceduresAnonymous surveys were collected using venue intercept procedures that have been reported in previous studies [21, 25].

Potential participants were asked to complete a survey concerning their

health related behaviors as they walked through the exhibit area of a

large gay pride festival in the Southeastern United States. For the

purposes of completing this study, two booths were rented in the display

area of the event. Participants were told that the survey was about

well-being and health care behaviors, contained personal questions about

their behavior, was anonymous, and would take 15-min to complete.

Eighty percent of men who were approached agreed to complete the survey.

Participant names were not obtained at any time. Participants were

offered $5 for completing the survey and an additional $5 was donated to

a local HIV service provider. MeasuresParticipants

completed self-administered surveys measuring socio-demographic

characteristics; health care insurance and access; PrEP use, awareness,

and interest; PrEP stigma and conspiracy related beliefs; and sex

behaviors. Demographics and Health CareParticipants

were asked to report their age, years of education, income, gender

identity, race/ethnicity, employment status, relationship status, sexual

orientation, HIV status, whether they had health insurance, whether

they had a health care provider, whether they had talked with a provider

about sexual health in past year, and whether they talked with a health

care provider about PrEP. Response set was a dichotomous Yes/No. PrEP Use, Awareness, and InterestParticipants

were provided with a standard definition of PrEP. Specifically, as part

of the instruction set, the survey read “PrEP (pre-exposure

prophylaxis) is when an HIV-negative person takes anti-HIV medications,

also known as antiretrovirals and more specifically Truvada, BEFORE

HAVING SEX to prevent HIV infection.” Participants then responded Yes/No to

each of the following: “Have you ever heard of PrEP?” (i.e., PrEP

awareness), “Do you know anyone who is taking PrEP?”, “Are you currently

taking PrEP?”, and “Would you be interested in taking PrEP?” PrEP Stigma and Conspiracy-Related BeliefsParticipants

were asked three items regarding PrEP stigma specifically focused on

stereotyping and two items regarding PrEP conspiracy beliefs. Stigma

items included: “PrEP will cause people to have more risky sex”,

“Instead of taking PrEP, people should just pick their partners

carefully”, and “PrEP is for people who are promiscuous (e.g., “slutty”

or “easy”)”; and conspiracy beliefs items included: “The CDC cannot be

trusted to tell gay communities the truth about PrEP”, and “When it

comes to PrEP, drug companies are lying and taking advantage of us.”

Response set for these items included Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (4).

Items were developed using three primary approaches: adaptation from

other measures of stigma and conspiracy beliefs [24], deduction from the HIV stigma framework [18],

and community feedback. Items were generated with a focus on conceptual

consistency, similar person-perspective for all items, caution with

negatively worded items, assessment of intended meaning, and appropriate

literacy level. Due to low scale reliability for the PrEP stigma items

(Cronbach’s α = .50), and for the conspiracy beliefs items (Cronbach’s α

= .69), items were treated as individual independent variables in all

analyses. For interpretation purposes, items were dichotomized as

disagree and agree, and presented as N’s and percentages in the table;

however, variables were treated as continuous in all analyses.

Participants were also asked, “Have you ever heard of the phrase

‘Truvada Whore”’? Response set was a dichotomous Yes/No. Sexual BehaviorParticipants

reported the number of male and female sex partners they had in the

last 6 months. Further, they were asked the number of times they had

engaged in anal intercourse with a man as the insertive and receptive

partner without condoms in the past 6 months. Participants also reported

the number of condomless vaginal sex acts they engaged in during the

past 6 months. An open response format was used. Data AnalysisParticipants were 387 men and 6 transgender women (N =

393) surveyed at a Gay Pride Festival in the Southeastern United States

in October 2015. Of these participants, 64 were removed due to

reporting HIV positive status, 2 were removed for identifying as

heterosexual and reporting no male sex partners, 39 were removed for

identifying as a race other than Black/African American or White, and 3

were removed for incomplete data, leaving N = 285

participants for all remaining analyses. Twenty-one participants

currently taking PrEP were removed from further analyses. In

total, N = 85 BMTW and N = 179 WMTW who reported HIV negative status and not currently on PrEP were included in primary data analyses. Descriptive

data including means and standard deviations, or numbers and

percentages were provided for all variables. Bivariate generalized

linear modeling (GZLM) with a binary logistic distribution was conducted

in order to assess variables relating to interest in PrEP. Estimates

that were significant at p < .10 were entered into

the multivariable analyses. The dependent variable was, “Would you be

interested in taking PrEP?” and had a dichotomous Yes/No outcome.

Analyses were run for the whole sample and separately for BMTW and

WMTW. Analyses were also completed for comparing variables between BMTW

and WMTW. In a post hoc analysis for further examining findings related

to PrEP interest, GZLM was used to evaluate the relationships between

PrEP/promiscuity related beliefs, PrEP interest, and sex behaviors.

Demographic and health care related variables were used as control

variables in analyses. Results were reported as odds ratios (OR) and

adjusted odds ratios (aOR). There were less than 5% missing data for any

given variable. PASW Statistics version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL)

was used for all analyses. ResultsFindings demonstrated that, on the whole, 44% of the sample was interested in PrEP with 53% (n = 45) of BMTW and 39% (n = 70) of WMTW reporting interest in using PrEP (X2[1] = 4.49, p <

.05). Forty-three percent of the sample had heard of PrEP on a prior

occasion. Having previously heard of PrEP was related to greater

interest in using PrEP for WMTW and for the total sample, but not for

BMTW. For BMTW, WMTW, and the total sample, knowing someone who was

taking PrEP was related to interest in using PrEP. Sociodemographics and PrEP InterestOn

average participants reported ‘some college’ as their highest level of

educational attainment, and educational attainment was not associated

with interest in using PrEP. A majority of the sample identified as male

(n = 258, 98%) and reported being currently employed (n =

199, 75%). Lower income (≤$30,000) was associated with increased

interest in using PrEP for WMTW and for the total sample, but not

specifically for BMTW. WMTW who were not in a relationship or who were

in a non-monogamous relationship were more likely to report interest in

using PrEP than WMTW who were in monogamous relationships, and similar

findings were observed for the total sample. Among WMTW, currently

having health insurance and a health care provider were associated with a

lower likelihood of being interested in PrEP. For the total sample,

having health insurance was related to a lower interest in PrEP, and,

among BMTW, having a health care provider was related to a lower

interest in PrEP (Table 1). Table 1Demographic characteristics of BMTW and WMTW attending a community event in the southeastern US | BMTW (N = 85) PrEP interest | BMTW | WMTW (N = 179) PrEP interest | WMTW | Total sample |

|---|

| |

| | |

|---|

| Interested (n = 45) | Not interested (n= 40) | N = 85 | Interested (n = 70) | Not interested (n = 109) | N = 179 | N = 264 |

|---|

|

| |

|

| | |

|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | OR (95% CI) | M | SD | M | SD | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|

|

|---|

| Agec | 30.58 | 12.33 | 32.83 | 11.96 | .99 (.95–1.02) | 31.93 | 12.93 | 39.46 | 15.27 | .96 (.94–.99)** | .97 (.95–.99)*** |

|---|

|

|---|

| BMTW (N = 85)

PrEP interest | BMTW | WMTW (N =179)

PrEP interest | WMTW | Total sample |

|---|

| |

| | |

|---|

| Interested (n = 45) | Not interested (n = 40) | N = 85 | Interested (n = 70) | Not interested (n = 109) | N = 179 | |

|---|

|

| |

|

| | |

|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR (95% CI) | N | % | N | % | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|

| Education (M, SD)c | 14.04 | 2.07 | 13.80 | 2.47 | 1.05 (.87–.1.27) | 14.51 | 2.17 | 14.87 | 2.19 | .93 (.81–1.06) | .95 (.85–1.06) | | Male | 45 | 100 | 39 | 97.5 | N/A | 69 | 98.6 | 105 | 96.3 | .81 (.43–1.54) | .71 (.38–1.33) | | Transgender Female | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | | 1 | 1.4 | 4 | 3.7 | | | | Incomec | | | | | .83 (.61–1.12) | | | | | .80 (.68–.96)* | .50 (.30–.82)** | | ≤$30,000 | 27 | 60.0 | 17 | 52.5 | | 35 | 50.7 | 35 | 32.1 | | | | > $30,000 | 18 | 40.0 | 19 | 47.5 | | 34 | 49.3 | 74 | 67.9 | | | | Employedc | 30 | 66.7 | 27 | 67.5 | .96 (.39–2.28) | 58 | 82.9 | 84 | 77.1 | 1.44 (.67–3.09) | 1.12 (.63–1.97) | | Relationship status | | No relationship | 27 | 60.0 | 27 | 67.5

32.5 | .93 (.37–2.34) | 44 | 62.9 | 49 | 45.0 | 3.05 (1.51–6.18)** | 2.06 (1.20–3.56)** | | In non-monogamous relationship | 4 | 8.9 | 0 | 0.0 | N/A | 11 | 15.7 | 9 | 8.3 | 4.16 (1.45–11.90)** | 3.68 (1.44–9.38)** | | In monogamous relationship (ref) | 14 | 31.1 | 13 | | | 15 | 21.4 | 51 | 46.8 | | | | Sexual orientationd | | Gay (ref) | 34 | 75.6 | 31 | 77.5 | | 63 | 90.0 | 94 | 87.9 | | | | Bisexual | 8 | 17.8 | 8 | 20.0 | .91 (.31–2.72) | 7 | 10.0 | 12 | 11.2 | .87 (.33–2.33) | .52 (.09–3.16) | | Hetero sexual | 3 | 6.7 | 1 | 2.5 | N/A | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | N/A | | | Currently have health insurancec(Yes) | 30 | 66.7 | 29 | 72.5 | .76 (.30–1.92) | 50 | 72.5 | 100 | 91.7 | .24 (.10–.56)** | .37 (.20–.68)** | | Have health care provider a (Yes) | 31 | 68.9 | 34 | 85.0 | .39 (.13–1.14)a | 56 | 81.2 | 102 | 93.6 | .30 (.11–.78)* | .31 (.15–.63) | | Talked with health care provider about sexual health past year (Yes) | 27 | 60.0 | 30 | 76.9 | .45 (.17–1.17) | 39 | 56.5 | 61 | 56.0 | 1.02 (.56–1.88) | .86 (.52–1.42) | | Health care provider has talked about PrEPb (Yes) | 11 | 24.4 | 10 | 25.0 | .97 (.36–2.61) | 9 | 13.0 | 15 | 13.8 | .94 (.39–2.28) | 1.06 (.55–2.01) |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 ap < .10 bSignificantly higher mean/percent among BMTW as compared with WMTW cSignificantly higher mean/percent among WMTW as compared with BMTW dBMTW significantly more likely to report being bisexual and less likely to report being heterosexual than WMTW PrEP Stigma, PrEP Conspiracy Beliefs, and PrEP InterestIn regards to PrEP related beliefs, 70% (N =

186) of participants agreed that PrEP would cause people to have more

risky sex; these beliefs, however, were not related to interest in using

PrEP. Believing that individuals should pick their partners more

carefully instead of taking PrEP (45%, N = 120

endorsed item) was related to a greater likelihood of not being

interested in PrEP for BMTW, WMTW, and the total sample. Twenty-three

percent (N = 60) of the sample believed that PrEP was for

individuals who were promiscuous, and this belief was associated with a

lack of interest in using PrEP for all groups. Overall, it is noted that

PrEP related stigma was related to numbers of sex partners, but not sex

behaviors, specifically. Among BMTW, believing that the CDC cannot be

trusted in their messaging regarding PrEP was associated with a lower

interest in using PrEP. Nineteen percent of the sample had heard of the

phrase “Truvada Whore”, however, having heard of this phrase was

unrelated to interest in PrEP (Table 2).

There were no significant differences across BMTW and WMTW regarding

responses to the PrEP stigma beliefs items. BMTW were, however, more

likely to report that the CDC cannot be trusted to provide accurate

information on PrEP than WMTW (56.5% vs. 43.5%, X2(1) = 10.5, p < .01). Table 2PrEP beliefs and interest among BMTW and WMTW attending a community event in the southeastern US | BMTW (N = 85) PrEP interest | BMTW | WMTW (N = 179) PrEP interest | WMTW | Total sample |

|---|

| |

| | |

|---|

| Interested (n = 45) | Not interested (n = 40) | N = 85 | Interested (n = 70) | Not interested (n = 109) | N = 179 | N = 264 |

|---|

|

| |

|

| | |

|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR (95% CI) | N | % | N | % | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|

| Have you ever heard of PrEP?c (Yes) | 28 | 62.2 | 18 | 45.0 | 2.01 (.85–4.79) | 60 | 85.7 | 62 | 56.9 | 4.55 (2.11–9.82)*** | 2.81 (1.64–4.82)*** | | Do you know anyone who is taking PrEP? (Yes) | 17 | 37.8 | 8 | 20.0 | 2.43 (.91–6.48) | 38 | 54.3 | 27 | 24.8 | 3.61 (1.90–6.84)*** | 2.99 (1.76–5.06)*** | | PrEP will cause people to have more risky sex | 34 | 75.5 | 27 | 67.5 | 1.49 (.58–3.84) | 45 | 64.2 | 80 | 73.4 | .65 (.34–1.25) | .89 (.67–1.19) | | Instead of taking PrEP, people should just pick their partners carefully | 21 | 46.6 | 25 | 62.5 | .69 (.47–1.02)a | 24 | 34.2 | 50 | 46.3 | .74 (.54–1.02)a | .77 (.61–.91)* | | PrEP is for people who are promiscuous (for example, “slutty” or “easy”) | 5 | 11.1 | 15 | 37.5 | .45 (.28–.74)*** | 9 | 12.9 | 32 | 29.9 | .58 (.40–.84)*** | .54 (.40–.72)*** | | The CDC cannot be trusted to tell gay communities the truth about PrEPb | 15 | 33.3 | 22 | 55.0 | .61 (.38–1.00)a | 17 | 24.2 | 25 | 23.8 | .96 (.68–1.37) | .88 (.67–1.15) | | When it comes to PrEP, drug companies are lying and taking advantage of us | 11 | 24.4 | 17 | 42.5 | .72 (.46–1.13) | 19 | 27.1 | 33 | 31.1 | .82 (.56–1.20) | .80 (.60–1.06) | | Heard phrase “truvada whore.” | 9 | 20.0 | 11 | 27.5 | .66 (.24–1.81) | 16 | 23.2 | 15 | 13.8 | 1.88 (.86–4.17) | 1.33 (.72–2.44) |

***p < .001 ap < .10 bSignificantly higher mean/percent among BMTW as compared with WMTW cSignificantly higher mean/percent among WMTW as compared with BMTW Sex Behaviors and PrEP InterestReporting

a greater number of sex partners was associated with interest in PrEP

for WMTW and the total sample, but was nonsignificant for BMTW. The

proportion of time condoms were used during both receptive and insertive

anal sex was not associated with interest in PrEP (Table 3). Table 3Sexual behaviors and PrEP interest among BMTW and WMTW attending a community event in the southeastern US | BMTW (N = 85) PrEP interest | BMTW | WMTW (N = 179) PrEP interest | WMTW | Total sample |

|---|

| |

| | |

|---|

| Interested (n = 45) | Not interested (n = 40) | N = 85 | Interested (n = 70) | Not interested (n = 109) | N = 179 | N = 264 |

|---|

|

| |

|

| | |

|---|

| In past six months: | M | SD | M | SD | aOR (95% CI) | M | SD | M | SD | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|

| Number of male sex partners | 3.38 | 4.78 | 2.23 | 2.52 | 1.11 (.96–1.29) | 5.21 | 7.42 | 2.55 | 7.02 | 1.06 (1.01–1.12)* | 1.07 (1.01–1.12)* | | Number of receptive, condomless anal sex actsb | 2.05 | 4.97 | .95 | 3.19 | 1.08 (.94–1.25) | 6.43 | 14.93 | 4.78 | 15.95 | 1.01 (.99–1.03) | 1.01 (.99–1.03) | | Number of insertive, condomless anal sexb | 3.14 | 6.75 | 1.55 | 4.95 | 1.05 (.96–1.16) | 4.59 | 8.52 | 6.67 | 22.45 | .99 (.97–1.01) | .99 (.98–1.01) | | Number of female sex partnersa | .56 | 1.79 | .50 | 1.75 | 1.02 (.80–1.30) | .12 | .66 | .05 | .22 | 1.44 (.66–3.13) | 1.10 (.87–1.39) | | Number of condomless vaginal sex acts | .51 | 1.84 | .43 | 1.38 | 1.03 (.79–1.35) | .03 | .18 | .42 | 2.33 | .70 (.33–1.47) | .94 (.79–1.11) |

*p <.05 aSignificantly higher mean/percent among BMTW as compared with WMTW bSignificantly higher mean/percent among WMTW as compared with BMTW Multivariable Models and PrEP InterestFor

the multivariable model among BMTW, believing that PrEP was for people

who were promiscuous remained the only variable associated with PrEP

interest. Specifically, the more likely BMTW were to believe that PrEP

was for promiscuous individuals the less interest they had in using

PrEP. In the multivariable model for WMTW, not being in a relationship

and being in a non-monogamous relationship versus being in a monogamous

relationship, not currently having health insurance, and having ever

heard of PrEP were associated with interest in PrEP. The same

relationships held for the multivariate model inclusive of the whole

sample and, in addition, lower age and believing that PrEP is for people

who are promiscuous were associated with reduced interest in PrEP.

Number of male sex partners did not remain associated with PrEP interest

in any multivariable model (Table 4). Table 4Multivariate models of factors related to PrEP interest among BMTW and WMTW attending a community event in the southeastern US | PrEP interest |

|---|

|

|---|

| BMTW (N = 85) | WMTW (N = 179) | Total sample (N = 264) |

|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|

| Age | N/A | .98 (.95–1.01) | .98 (.95–1.00)a | | Income | N/A | .69 (.29–1.68) | .68 (.34–1.35) | | Relationship status | | No relationship | | 2.72 (1.20–6.17)* | 1.90 (1.02–3.53)* | | In non-monogamous relationship | N/A | 4.03 (1.11–14.66)* | 4.68 (1.49–14.73)** | | In monogamous relationship (ref) | | | | | Currently have health insurance (Yes) | N/A | .23 (.07–.78)* | .34 (.16–.72)** | | Have health care provider (Yes) | .46 (.15–1.44) | 1.06 (.27–4.09) | N/A | | Have you ever heard of PrEP? (Yes) | N/A | 4.36 (1.75–10.34)** | 2.99 (1.59–5.65)** | | Instead of taking PrEP, people should just pick their partners carefully. | .85 (.56–1.30) | .83 (.54–1.28) | .85 (.64–1.14) | | PrEP is for people who are promiscuous (e.g., “slutty” or “easy”). | .51 (.30–.87)** | .68 (.43–1.08) | .56 (.39–.78)** | | The CDC cannot be trusted to tell gay communities the truth about PrEP. | .82 (.46–1.44) | N/A | N/A | | Number of male partners | N/A | 1.02 (.97–1.08) | 1.03 (.98–1.09) |

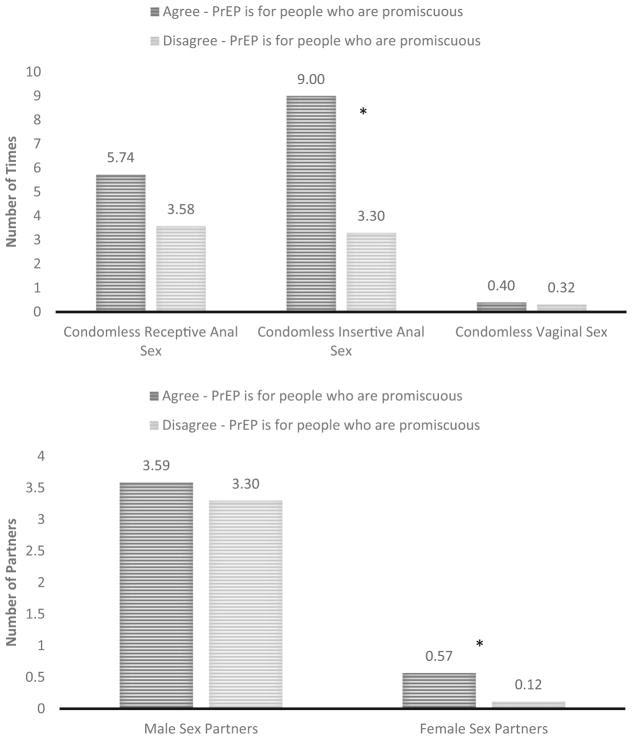

**p < .01, *p <.05 ap = .05 Post Hoc AnalysesGiven

the strong relationships observed in the multivariable models between

endorsing promiscuity related to PrEP and lack of interest in using

PrEP, data analyses were completed to investigate these results.

Findings demonstrate greater sexual risk taking among individuals who

believe that PrEP is for people who are promiscuous; individuals who

endorsed this belief reported greater numbers of condomless insertive

anal sex acts (OR = .98[.96–.99]) and female sex partners (OR =

.73[.55–.97]). There were no differences for number of male sex partners

(OR = .99[.95–1.04]), condomless receptive anal sex acts (OR =

.99[.97–1.01]) and condomless vaginal sex acts (OR = .99[.84–1.14]) (Fig. 1). Sexual risk behaviors and endorsement of PrEP being related to promiscuity DiscussionFindings

from the current study highlight multiple areas of importance for

understanding how PrEP is received by communities in need of HIV

prevention options. Multiple noteworthy outcomes were identified,

including low levels of PrEP use, moderate levels of interest and

awareness in PrEP, and a strong relationship between endorsing

promiscuity as being related to PrEP use and lack PrEP interest. Other

findings of importance include the relationship between younger age and

greater PrEP interest, and the relationship between negative beliefs

about PrEP and greater sexual risk taking. Given the state of the HIV

epidemic among MTW in the US, it is imperative that researchers, health

care providers, and policy makers understand how prevention technologies

such as PrEP are received by communities, and this study offers

important insights in these areas. In the current study, levels of PrEP use and awareness were alarmingly low. It is known that PrEP uptake has been slow [10],

and the present study’s findings suggest that this pattern continues to

persist. Further delays in these areas, put simply, costs lives -there

is urgent need to bolster efforts to improve awareness and

accessibility. Importantly, however, and similar to prior research, it

appears that interest in PrEP is at least moderate [26].

We also note that PrEP interest was greater among BMTW than WMTW.

Greater interest in PrEP may be the result of the relatively higher HIV

prevalence among communities of BMTW compared with that of communities

of WMTW. Understanding perceptions of HIV risk between BMTW and WMTW may

offer insight into the observed higher interest in PrEP among BMTW.

Moving forward, researchers, policy makers, and key stakeholders must

prioritize better understanding the key drivers of the gap between PrEP

interest and uptake (e.g., [27, 28]). In particular, the extent to which structural and sociocultural barriers contribute to this gap warrants further research. Although

the majority of the sample reported current health care coverage, a

health care provider, and had talked with a provider about their sexual

health, a significant minority of these individuals did not report

having sufficient health care access and individuals lacking health care

coverage were more likely to be interested in PrEP. Individuals with no

health care coverage may report greater interest in PrEP due to,

potentially, having fewer alternative options for HIV prevention than

individuals with health care coverage. Meaning, health care coverage may

serve as a proxy variable for social capital, which is related to one’s

ability to access economic goods and social benefits (e.g., condoms, or

greater power in negotiating safer sex). With greater access to various

prevention options, PrEP may be less appealing, however, further

research in these areas is warranted. As more biomedical HIV prevention

options emerge that rely on access to and continued involvement with

health care systems, including health care coverage and medical

providers, it will be imperative that advances in infrastructure

co-occur. Without these advances, biomedical prevention options will

remain out of reach for many. On the whole, the findings suggest that

the basic foundation for successful implementation of PrEP remains

under-developed. In

regards to PrEP beliefs, the majority of the sample reported believing

that PrEP would cause people to have more sex partners. Although

evidence from PrEP studies demonstrate mixed findings regarding the

effect of PrEP on sexual risk taking [29–31], based on the current data, there exists the perception that PrEP will affect

sexual risk taking. It is possible that this belief can have an effect

on how people perceive who should or should not take PrEP [32]. Moreover, and importantly, it is known that sex in monogamous relationships is a risk factor for HIV transmission [33],

which makes the belief that PrEP is for people who have many sex

partners particularly problematic. Also, PrEP is an important form of

prevention for individuals in HIV serodiscordant relationships; in this

case, HIV prevention strategies are not associated with number of

partners but rather the prevention of transmission from sex with a

partner who is known to be living with HIV. In either case, the

perception that PrEP is for people with multiple sex partners overlooks

the need for PrEP for people with one or limited numbers of partners.

Addressing the various ways in which individuals process sexual risk

taking and the need to take PrEP [34, 35] is a central component to effective messaging behind the promotion of PrEP. A

large minority of the sample believed that PrEP was for people who are

promiscuous, and this belief was associated with a lack of interest in

PrEP. Furthermore, believing that PrEP was for people who are

promiscuous was more likely to be reported among participants with

greater sexual risk taking. These findings suggest that individuals who

report high levels of sexual risk are most impacted by beliefs that PrEP

is associated with promiscuity. Disassociating PrEP from perceptions of

promiscuity is likely important for improving uptake. Further, PrEP

interest was not associated with the belief that PrEP

would cause people to have risky sex. Based on the findings, it appears

that there is an important distinction between risky sex and sexual

promiscuity when endorsing stigma around PrEP use. It is possible that

the concept of promiscuity, in general, is evaluated negatively, whereas

evaluations regarding sex behaviors do not engender the same negative

perceptions. This slight, yet seemingly important, distinction appears

to be meaningful in understanding PrEP interest. Public health messaging

should take care to highlight the use of PrEP for those who are

sexually active regardless of frequencies of sex partners and behaviors.

Targeting those who report multiple sex partners as priority candidates

for PrEP likely further stigmatizes those who are taking or are

interested in taking PrEP, and may discourage others who could benefit

from PrEP from seeking it out [36].

Administering routine screenings of PrEP need to all people who are

sexually active may promote the de-stigmatization and normalization of

PrEP use. Data

from the current study also highlight an important age disparity in

PrEP interest. Older participants were less likely to report an interest

in PrEP than younger participants. There is considerable focus on HIV

prevention among youth populations due to increasing HIV incidence among

this group and federal funding priorities for prevention and treatment

tend to target youth populations. This strong focus leaves a void for

populations at-risk for HIV who have aged out of targeted groups [37]. Due to the nature of HIV epidemiology, HIV prevalence increases quite dramatically among older age cohorts [38]

and therefore, although incidence might not be as dramatic among older

populations compared with younger, older MTW age groups have very high

prevalence rates of HIV. Messaging for PrEP must be careful to not only

include communities with high HIV incidence but also broad target groups

to promote inclusion. Although

conspiracy-related beliefs regarding PrEP were largely unassociated

with PrEP interest, a large minority of the sample endorsed these

beliefs, and for BMTW there was a trend towards conspiracy beliefs being

associated with PrEP interest. Undoubtedly, the history of unethical

treatment including serious physical and emotional abuse of

race-minority populations in medical studies in the US and abroad has

given way to a general mistrust of medicine and medical establishments

for many individuals. These beliefs are prominent in the HIV treatment

landscape [23, 39, 40].

As HIV prevention moves more towards biomedical approaches to slowing

the epidemic, developing strong relationships and improving the general

social standing of medical establishments, in particular in marginalized

communities, will be critical for product scale up. LimitationsThe

current study relied on self-reported information and, therefore, may

be prone to social desirability biases. Data come from a sample of BMTW

and WMTW whose responses may or may not be generalizable to the larger

population. Data were also cross-sectional which prevents causal

relationships from being evaluated. Low scale reliability suggests that

survey items tapped into subcomponents of stigma and conspiracy

beliefs—further research is needed to advance the psychometrics of this

novel area of inquiry. Our measure of PrEP stigma primarily focused on

promiscuity; however, further study in additional and related areas is

warranted. For example, the possibility of PrEP being associated with

intravenous drug use or minority sexual orientation as a barrier to use

is an important area of future research. The extent to which interest in

using PrEP serves as a barrier or facilitator to seeking out PrEP is

unknown and further research is needed to discern the extent to which

PrEP interest is related to uptake of PrEP. ConclusionsThe

potential for PrEP to slow the HIV epidemic has been hailed as one of

the most significant breakthroughs in the field of HIV prevention. Since

FDA approval, however, PrEP uptake has been slow and mired with

challenges relating to roll-out and accessibility. Advances in

biomedical prevention will not have a population-level effect on HIV

prevention without concurrent changes in structural (e.g., health care

infrastructure) and sociocultural areas (e.g., beliefs about PrEP).

Efforts to implement biomedical forms of HIV prevention must more

strongly and comprehensively focus on addressing the gap between

developing biomedical prevention options and making these options

accessible and sought after. AcknowledgmentsFunding This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01MH094230, R01NR013865, T32MH074387, and R01DA033067. References2. Purcell

DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A, Prejean J, Stein R, Denning P, et al.

Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the

United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:98–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3. Matthews

DD, Herrick AL, Coulter RW, Friedman MR, Mills TC, Eaton LA, et al.

Running backwards: consequences of current HIV incidence rates for the

next generation of black MSM in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1158-z. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]4. Grant

RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al.

Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with

men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5. McCormack

S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure

prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD):

effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label

randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]6. Goedel

WC, Halkitis PN, Greene RE, Hickson DA, Duncan DT. HIV risk behaviors,

perceptions, and testing and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

awareness/use in grindr-using men who have sex with men in Atlanta,

Georgia. JANAC. 2016;27(2):133–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]7. Dolezal

C, Frasca T, Giguere R, Ibitoye M, Cranston RD, Febo I, et al.

Awareness of post-exposure prophylaxis (pep) and pre-exposure

prophylaxis (PrEP) is low but interest is high among men engaging in

condomless anal sex with men in Boston, Pittsburgh, and San Juan. AIDS Educa Prev. 2015;27(4):289–97.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]8. Eaton

LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal

awareness and stalled uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among at

risk, HIV-negative, black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(8):423–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]9. Smith

DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, Stryker JE, Hall HI, Prejean J, et al.

Vital signs: estimated percentages and numbers of adults with

indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV

acquisition—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(46):1291–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]10. Mayer

KH, Hosek S, Cohen S, Liu A, Pickett J, Warren M, et al. Antiretroviral

pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation in the United States: a work in

progress. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(4 Suppl 3):19980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]11. Auerbach

JD, Hoppe TA. Beyond “getting drugs into bodies”: social science

perspectives on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(4 Suppl 3):19983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]12. Haire BG. Preexposure prophylaxis-related stigma: strategies to improve uptake and adherence—a narrative review. HIV/Aids. 2015;7:241–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]13. Calabrese

SK, Underhill K. How stigma surrounding the use of hiv preexposure

prophylaxis undermines prevention and pleasure: a call to destigmatize

“Truvada Whores” Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):1960–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]14. Oldenburg

CE, Mitty JA, Biello KB, Closson EF, Safren SA, Mayer KH, et al.

Differences in attitudes about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among

stimulant versus alcohol using men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1226-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]17. Stigma EG. Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc; 1963.[Google Scholar]18. Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]19. Herek GM. AIDS and stigma. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42:1106–16. [Google Scholar]20. Underhill

K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, Holcomb R, Calabrese SK, Operario D, et al. A

qualitative study of medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and

risk behavior disclosure to clinicians by US male sex workers and other

men who have sex with men: implications for biomedical HIV

prevention. J Urban Health. 2015;92(4):667–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]21. Eaton

LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, et al.

The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care

engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):e75–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]22. Maulsby

C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, et al. HIV

among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a

review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):10–25.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]23. Bogart

LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are

related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among african american

men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(5):648–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]24. Bogart LM, Thorburn S. Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(2):213–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]25. Eaton

LA, Driffin DD, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, Cherry C.

Psychosocial factors related to willingness to use pre-exposure

prophylaxis for HIV prevention among Black men who have sex with men

attending a community event. Sexual Health. 2014;11(3):244–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26. Cohen

SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, Doblecki-Lewis S, Postle BS, Feaster DJ, et

al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex

with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP

demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):439–48. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar]27. Krakower

D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived

barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in

care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]28. Calabrese

SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of

patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV

pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk

compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):226–40. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar]29. Grov

C, Whitfield TH, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Willingness to

take PrEP and potential for risk compensation among highly sexually

active gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(12):2234–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]30. Blumenthal J, Haubrich RH. Will risk compensation accompany pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV? Virtual Mentor: VM. 2014;16(11):909–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]31. Volk

JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, Blechinger D, Nguyen DP, Follansbee S, et

al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure

prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1601–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]32. Adams

L, Balderson B, Packett B, II, Brown K, Catz S. Providers’ perspectives

on prescribing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV

Prevention. HIV Spec. 2015;7(1):18–25. [Google Scholar]33. Sullivan

PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of

HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men

in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153–62.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]34. Gamarel

KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM)

in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(2):177–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]35. Brooks

RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, Lei-bowitz AA.

Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure

prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in

HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1136–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]36. Calabrese

SK, Underhill K, Earnshaw VA, Hansen NB, Kershaw TS, Magnus M, et al.

Framing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the general public: how

inclusive messaging may prevent prejudice from diminishing public

support. AIDS Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1318-9. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]37. Davis T, Zanjani F. Prevention of HIV among older adults: a literature review and recommendations for future research. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1399–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]38. Matthews

DD, Herrick AL, Coulter RW, Friedman MR, Mills TC, Eaton LA, et al.

Running backwards: consequences of current HIV incidence rates for the

next generation of black MSM in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):7–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]39. Hutchinson

AB, Begley EB, Sullivan P, Clark HA, Boyett BC, Kellerman SE.

Conspiracy beliefs and trust in information about HIV/AIDS among

minority men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(5):603–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]40. Gillman

J, Davila J, Sansgiry S, Parkinson-Windross D, Miertschin N, Mitts B,

et al. The effect of conspiracy beliefs and trust on HIV diagnosis,

linkage, and retention in young MSM with HIV. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]Similar articles in PubMedCited by other articles in PMC

This Email has an A.I. Boomerang Respondable Status:

Likely To Receive A Response.

BoomerangRespondableLikelyto receive a response

Dear,

BTW:

The Use of the "Fuck" Word in this Professionals Business

Correspondence Is A Standard Established by the Most Popular Recognized

Professional's Social Media Networking Site, This Stanard Apples

that actual "In Operation" Company Named Profiles Are Accepted On That

Site. This includes [ but not limited to ], "Fuck Cancer with a website

of http://FuckCancer.Org ], "Fuck Yeah Astrophysics with a website of http://FuckYeahAstrophysics

[, "Fuck Racism which has a similarly named website ], and "Fucked Up

Design having also a similarly named website ],

"FuckedUphuman.net" is just an extension of this standard that is

established on LinkedIn and applies across the entire internet [

UNCONDITIONALLY TRUE ]

Ms.

Keady,. There is no sense in denying what you all did to me in that you

intentionally created the chaos that collapsed the attempted startup of

"The Awesome Kramobone Glows And Blows Playroom which has a web presence

of http://AwesomeKramoboneplayroom.school/.BasicHumanNeeds/.

In that, I was engaged in the educational aspects of "adult consensual

practices" as it is associated to sexual experiences. What is found in

this document is alarming in that discontinuance of a disturbing trend

that you are at the hands of creating WILL CAUSE A PROVABLE UPTICK IN

HIV INFECTIONS WITHIN THE DENVER COMMUNITY with the void that you all

perpetrated based on HATE against me! PreP was, of course, one of

the topics that were being discussed within the community that I was

seeking and dissemination the knowledge of this option to persons who

are having sexual activity experiences within the community. At

the time, even though the CDC was extremely tarty with their now [ U=U ]

campaign, that among the community knowledge was this fact.

In

so that you could not accept the fact because you had been in the

continuous habit of breaking clients privacy,, hating on them on social

media, harassing them in any unlawful matter to interrupt their sexual

encounters, you all have been WRONG! You are criminally and

civilly guilty of mismanagement of your contracted services to the HIV

Community,. And you all know it! SHAMEFUL!

Your

place for all time human history stands here Although the

Glassdoor reviews for Colorado Health Network did not appear until 14

days after I had to leave the Denver Area for my hometown due to the

lack of community concerns you all have for my continued presence and

influence [ WHICH WOULD ACTUALLY SAVE AND PREVENT HIV INFECTIONS WHILE

YOUR PARADIGM OPERATIONS INDUCES MORE ] HOW CAN YOU ALL SLEEP AT NIGHT

KNOWING WHAT YOU HAVE DONE?

Conclusions The

potential for PrEP to slow the HIV epidemic has been hailed as one of

the most significant breakthroughs in the field of HIV prevention. Since

FDA approval, however, PrEP uptake has been slow and mired with

challenges relating to roll-out and accessibility. Advances in

biomedical prevention will not have a population-level effect on HIV

prevention without concurrent changes in structural (e.g., health care

infrastructure) and sociocultural areas (e.g., beliefs about PrEP).

Efforts to implement biomedical forms of HIV prevention must more

strongly and comprehensively focus on addressing the gap between

developing biomedical prevention options and making these options

accessible and sought after.:

YOU HAVE AN OBLIGATION TO RECONCILE WITH THE TRUTH OF THESE MATTERS TO HAVE YOUR WEB PRESENCE AT FUCKEDUPHUMAN.NET

REMOVED WHEN COLORADO HEALTH NETWORK NO LONGER IS IN A NEED TO SERVICE

THE HIV COMMUNITY [ FUTURE TIME 5 / 10 YEARS ], YOU WILL BE LOOKING FOR A

JOB, AND POTENTIAL EMPLOYERS WILL DISCOVER THE CONTENT IN YOUR NAME AND

WONDER WHY YOU ARE LISTED INDIVIDUALLY @ FUCKEDUPHUMAN.NET AND SKIP ON DOWN THE ROAD TO THE NEXT RESUME / PERSON / CANDIDATE,

|

|

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+